Making Tests Meaningful

Making Tests Meaningful

“Take me to the test, and I the matter will reword.” — William Shakespeare

“Too much testing can rob school buildings of joy and cause unnecessary stress.” — Arne Duncan

“Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.” — Albert Einstein

When a student gets an “A” on a test, it can mean 1) he has truly and deeply learned the material, or 2) he did well on the test, but will have forgotten most of it within a week or two. The test doesn’t distinguish between the two. In fact, it is incapable of doing so. Tests by themselves do not measure learning.

Students often cram the night before a test. They then feel successful when their score is high, regardless of how much they have actually learned. Teachers, too, often fall for the illusion — having a class score well on a test feels good. When a student gets A’s on one test after another, this surely means he is learning, right?

Unfortunately, it does not. Doing school is a simulation of learning, and tests are one of the places where the simulation is the most compelling. We need to find a way to break the cram/regurgitate/forget cycle of testing and replace it with a mechanism that is an effective part of the learning process. We need to make tests meaningful.

8.1 The Lure of False Positives

8.1 The Lure of False Positives

If we are being honest, we have to acknowledge that tests measure only how many questions a student can answer correctly at that moment. How the student acquired this knowledge, how long he will retain it, and how meaningful it is to the him are not being measured. Since there is no reliable way to know what a test score means in terms of learning, it is important to know what it probably means.

When a student fails a test, there is a strong possibility that he didn’t understand the material. Let’s call that a true negative. But it is also possible that other factors, like test anxiety or personal issues, may have created a false negative: he knows the material, but the test doesn’t show it. When I was in graduate school, I had knee surgery. Several days later, I failed a test in a course in which I had aced every test before and after this one. The injury and medical procedure affected me in unexpected ways. To this day, I have no idea how that happened, but it was a classic false negative.

As for people who do well on tests, a true positive means that a good test score represents learning. A false positive would mean a high score, but little or no genuine learning. From the self-reporting of my students, false positives (or partial false positives: a student aces a test but has only learned some of the material) are commonplace. They may even be the norm. Studies of long-term retention rates confirm the breadth of misleading test scores. Students who have exemplary test scores in class after class are somehow forgetting what they “learned” in a matter of weeks or months. That’s not learning, but it certainly looks like it - a classic symptom of doing school.

Trusting that high test scores mean that learning has taken place is like asking a class “Are there any questions?” and assuming that when no one has any questions it means that everyone understands the material. They are both false positives.

It is a humbling experience to realize that you cannot trust or control the meaning of test scores. There is no way to force good test scores into true positives. If a student is proficient at doing school, doing well on tests will not represent genuine learning. All a teacher can do, all he should do, is shape the classroom culture into one where the student prefers learning over cramming and forgetting, prefers honesty over the dishonesty of doing school.

A realistic teacher will recognize that only the student can know whether he has been learning or cramming. This is as it should be if the student is to truly steer his own learning process.

The lure of the false positive for a student is that it seems quicker to cram for a test and get a high score than to actually learn the material. If a student is doing school, a false positive counts as much as a true one. The goal of school for him is to get good grades, and a test score is equally valid whether it represents genuine learning or not. Unfortunately, this point of view is pervasive.

What we should hope for is more and more true positives — that is, high test scores that occur because of solid understanding of the material. Unfortunately, many teachers aren’t aware of the existence of false positives. They can’t or won’t distinguish between true and false positives. Their response when students do badly on a test is to try to help them raise those scores. This can happen while still remaining blind to the difference between self-directed learning and doing school.

The question we should be asking is not how to raise low test scores, but how to make the learning process so effective that high test scores actually mean something. We need to see whether test-taking can become a meaningful, even an essential part of the learning process.

8.2 The Limitations of Testing

8.2 The Limitations of Testing

A close examination of the traditional practice of testing reveals an often messy picture of unintended and unwanted side effects. It is critical to recognize the limitations of tests so we can minimize the collateral damage that results when we use these imperfect tools. With care, we can even turn them to our students’ advantage and transform testing into a useful and refined tool.

Testing alone does not measure learning.

As described above, tests measure how many questions a student can correctly answer at that moment. It says nothing about how much will be retained — that is, truly learned. There is a profound difference between knowledge that resides in working memory, which is active and retrievable for a matter of days or weeks, and knowledge that has been transferred to long-term memory and therefore is integrated into what the student really knows.

Testing does not cause learning.

Cows don’t gain weight faster when you weigh them more frequently or more accurately. A child’s fever won’t be affected if you take his temperature, regardless of how often you do it or how precise your thermometer is. Once you have measured a student’s knowledge with a test, you are still left with the question, “Now what?”

In fact, test-taking can actually detract from a student’s understanding of the material. The the anxious anticipation of an upcoming test can undermine the motivation to learn. When a student crams for a test, he is jamming as much content as possible into his working memory in the hopes that he will be able to retrieve it during the test. He is not concerned about whether he will still know it a year from now. The learning process has been displaced by something much less meaningful.

Testing distorts student motivation.

The more a student values the score on a test, the more the purpose of working becomes getting answers right. The ability to take chances, make mistakes, and learn from them shrinks accordingly. Real intellectual growth requires that kind of risk-taking and stretching into the unknown. A person who is risk-averse is not likely to be creative in the learning process. Tests encourage students to be risk-averse.

Poor test grades generate shame or anger.

Doing badly on on a test is a blow to a student’s self-esteem and self-confidence. When a student gets low grades on test after test, it is difficult not to “take it personally” and react with emotions that are counterproductive to learning. When a student stuffs a test that he did badly on into his backpack because he doesn’t want anyone to see it, it is unlikely that he will learn from the mistakes that he made.

Poor test grades solidify the belief in fixed attributes.

When a student consistently gets low scores on tests, an extremely common response is to believe that this is a measure of his intelligence, and that there’s nothing that can be done about it. The tendency for the student is to see herself as stupid or not good at math. Once that fixed mindset is established, his expectation of success vanishes, along with his motivation. This is counterproductive to becoming an effective learner.

Test anxiety does real damage.

Many students find their test scores affected, sometimes dramatically, because they are panicking and not thinking clearly. Under these circumstances, the test cannot accurately show you how much that student knows. Test anxiety also has a broader negative impact on the student, because panic attacks, especially when they are chronic, can have lasting effects on a student’s personality and posture in the classroom. Given the number of classes a student is taking, these bouts of panic are probably happening fairly frequently. Test anxiety can dramatically affect how much the student enjoys school and the learning process.

Tests often measure the ability to function well under intense pressure, even panic. This is especially true when we haven’t allowed enough time for the students who are slowest to finish at their own pace. We must ask ourselves whether the skill of answering questions under pressure is one that we hold to be important and want our students to excel at.

Tests reinforce the teacher-dominated power structure in classrooms.

How many times have you had legalistic struggles over how many points a student got on a test? When that happens, you and the student are not on the same side. This has a corrosive effect on your ability to be a mentor and facilitator in the student’s self-directed learning. After all, you are the one writing and scoring the tests, and therefore you are the one who controls the grades.

8.3 Redefining the Purpose of Testing

8.3 Redefining the Purpose of Testing

More than any other structure found in the classroom, testing reveals the working educational philosophy of the teacher and the school. For example, in a traditional classroom where the Curriculum Transfer Model dominates, and where the purpose of school is to transfer the course content into the minds of students, tests exist to measure how well that transfer has been accomplished. They are therefore designed and graded with the intent of sorting students along a scale of being more and less successful at that task.

Consider a typical test being given in this traditional manner. The test is written in such a way that only a few students are expected to answer all the questions correctly. That is because 1) so much curriculum has been covered that only a few students have actually mastered all of it, and/or 2) the test has been constructed so that students will be sorted along a bell curve and only a few students are intended to get all the questions correct. Both of these causes violate the Prime Directive — they have interfered with the self-directed learning of all the students who didn’t get A’s on the test.

Clearly, if we believe that the purpose of school is to prepare students to live their lives well, our testing system must change to serve that purpose. That preparation includes every student genuinely learning the knowledge and skills that he needs to know in life. To that end, tests must be designed to determine how well a student has independently mastered that content and only that content. A test that is used strictly for this purpose is called a “norm-referenced” assessment. The Prime Directive dictates that all tests should be designed to serve this purpose.

Notice that a comparison with how well other students have mastered the material plays no role in such a testing system. Grading to a curve to get the right distribution of A’s and B’s is forbidden. Each individual student’s assessment stands alone.

But if we are only testing the essential learning goals, aren’t we “dumbing down” the course? We would be if we were still requiring every student to learn the same content to the same depth at the same time. But differentiation frees us from that arbitrary constraint. Since some students — given their backgrounds, abilities, and motivation — are clearly capable of mastering all of content covered in the traditional test above, that full range must be made available to them.

In this scheme, then, every student learns what is essential to know, and those students who are able to dive in deeper, for whatever reason, are free to, and encouraged to do so.

And what of the argument made above that tests don’t measure learning? It rests on the premise that false positives — acing a test and not learning very much — is acceptable to students. This is, of course, true for a student who is doing school; the high test score is the highest priority, and if he gets an “A” he has met it. But what if he is not doing school? When self-directed learning becomes the bedrock of the classroom culture, when it is the common purpose of students and teacher alike, then the fact that a high test score can be false positive becomes much less important. It is only one source of feedback among many, and when it is inconsistent with other, more realistic feedback, the student knows that he still hasn’t mastered the learning goals, even when he does well on a test. If he cares about learning, a false positive won’t deceive him because he no longer wants want to be deceived.

Many of the problems described in the last section arise from the way tests are traditionally used. They typically follow a unit of study and are considered results. Once the test has been taken, the class moves on to the next unit. The teacher may review the test with the class, but there is very little opportunity for a student to do anything about a poor grade. In educational jargon, these are called summative tests. They serve little or no purpose in the learning process itself. They are merely reporting the status of each student’s learning. Unfortunately, as we have seen, this leads to a number of unspoken consequences that have serious negative effects on students and how they learn.

There is an alternative. Tests which are integrated into the learning process can serve as important feedback that helps a student steer his learning. These are called formative tests.

A good analogy for this approach is how Girl and Boy Scouts earn merit badges. They are given a specific goal and some tools for reaching it. Once they feel they are ready, they are tested. If they don’t succeed in showing mastery of the learning goals, they aren’t given a grade. Instead, they now know specifically what they haven’t learned yet, and they work on that. When they are ready, they are tested again. If they are successful, they get a patch representing that goal, and they move on to the next merit badge topic.

Similarly, if tests are to be integrated into the learning process, they must not only measure how well a student has mastered the material, but must also serve as feedback about what a student still needs to learn. Unlike summative tests, which are given at the end of the learning process, formative tests are built into the learning process. They are the starting point of helping a student to learn from his mistakes. Tests identify specifically what he has not yet mastered.

The key word in the last sentence is “yet”. When tests are used in this way, the student knows that if he is struggling at the time of the test, he will be able to continue working on the same material until he is no longer struggling. For a student who hasn’t yet mastered the material, it is simply the first assessment, which leads directly to remediation, focussing intensely on the material he knows he must still master.

8.4 The Benefits of Formative Tests

8.4 The Benefits of Formative Tests

"I never crammed for tests. Even if I did poorly on a test I would do a test resubmittal which would allow me to truly understand the problems that I had missed. Allowing test resubmittals really made me understand the material and be a better student." —Bill Z., student

Formative tests have a number of profound advantages over summative tests, including the following:

Formative tests provide important learning experiences.

When a test is “summative”, the student takes it, gets a grade, and the process ends. There is little opportunity to grow academically from the experience. On the other hand, a “formative” test, one that provides a chance to analyze the results and learn from them, is a fundamental building block of self-directed learning. The test offers feedback to help the student focus his attention on exactly what he still needs to learn. This part of the learning process may be one of the most effective. It requires classroom structures that give the students the opportunity to look carefully at their mistakes and do the necessary work to learn from them.

Tests can be a measure of the effectiveness of the learning process.

If a student feels the need to cram at the time of a test, it is a symptom of a learning process that needs correction — perhaps the student is not getting enough conversational learning or he needs more opportunities to practice a new skill. On the other hand, if the learning process is working well, a student may not need to study much for a test. Cramming, in fact, may become an obsolete behavior. His readiness to show what he knows builds and grows throughout the unit, rather than occurring in a burst of activity at the end. Knowledge that is built steadily over time — and is obtained as a sequence of learning goals that are met successfully — is much more likely to be integrated into the student’s mind and be truly learned.

Tests can provide an overview of the material being learned.

Preparing for a test provides an opportunity for the student to step back from the work he has been doing day by day and synthesize the material into a coherent whole. When the class slows down and reflects on what has been happening over the past week or two, concepts or skills that were new and perhaps not solidly understood can now be seen as steps along the way — steps which make more sense in retrospect than they did when they were first introduced.

Tests can inform the teacher whether the pace of the class has been appropriate.

When a whole class does badly on a test, that tells you that they weren’t ready as a group. This can happen when the pace is too quick and there hasn’t been enough time for everyone to digest the new material and work with it. It can happen because the scope of the unit was too large, and pieces have been forgotten or not synthesized into the whole. It can also happen when there has been insufficient time for the students to gain the necessary overview of the unit to make the pieces meaningful to them. In any case, the test can be seen as a snapshot of the learning process at that moment.

Tests can inform an individual student whether his proficiency level is sufficient to move on.

Tests should occur when the body of students have mastered the material and are ready to take on the next topic. When that happens, there will often be at least a few students who haven’t reached that level of mastery. Tests can tell them, in a non-judgmental way, that they need to do more work. If the structure of reviewing tests is functioning well, a student will discover precisely what aspects of the material he still needs to learn. This will drive the remediation process.

Tests can help cultivate grit.

“Fall down seven times, stand up eight.” — Japanese proverb

One of the unintended casualties of traditional test-taking is student tenacity. Imagine you are a student who does badly on tests, say in algebra. When you get a test back with a low score, you put it away and move on to the next unit with the rest of the class. Because there is no mechanism for learning from your mistakes, you are prevented from responding to the problem, whatever its cause. You are, in effect, being trained to acquiesce in the face of failure.

This experience is, of course, demoralizing and even humiliating, especially if it happens over and over. Equally bad, it is squandering an opportunity to learn to have grit in the face of adversity; students are trained not to have tenacity, to stand back up and figure out how to recover. This problem is being experienced by countless students every day in schools everywhere.

Remediation gives a student the opportunity to internalize the essential character traits of optimism and tenacity, (“I can learn this if I keep trying”). He is practicing the ability to see mistakes and failure as feedback. Having grit in the face of negative feedback is an essential attribute of self-directed learners. Without it, the motivation to persevere when the going gets tough dwindles, and the learning process is stymied.

Remediation helps a student learn to push through self-imposed ceilings on his academic success. He is thus being trained in a growth mindset, in the belief that effective effort leads to success. In so doing, his is also practicing a life skill that is important in every future endeavor.

8.5 Separating Concepts From Skills

8.5 Separating Concepts From Skills

It is useful to distinguish between what students should know — concepts — from what they should be able to do — skills. The remediation of these two classes of learning goals is often quite different. Testing the two separately can therefore lead to the appropriate remediation of each. Concepts and skills can be assessed as two parts of a single test, or, if the combined time to take both assessments exceeds a single class period, they can be given as separate tests on different days.

Another advantage of separating concepts from skills occurs when they are graded separately. Both your student and you will gain feedback on whether he is struggling with the overarching ideas or with specific skills. Over time, this feedback will contribute to a better understanding of a student’s academic strengths and weaknesses. It can be used to reshape his learning strategies for concepts or skills. If, for instance, his concepts test scores are lower than those from his skills tests, it may mean that he isn’t reading well or is skimming over new vocabulary without really understanding it. Similarly, low skills tests scores can lead to isolating the difficulty he is having with a specific subskill, like reading a story problem carefully or creating good research notes. Having one assessment for both concepts and skills can make discerning the nature of such problems more difficult.

8.6 The Functions of Remediation

8.6 The Functions of Remediation

Remediation is needed whenever a student hasn’t mastered essential learning goals. The overarching purpose of remediation is for a student to learn from his mistakes. However, there are a number of specific strategies that make this phase of the learning sequence more effective. Good remediation will include some or even all of the following:

Isolating the difficulty.

For a student to be successful at any complex task, he must first master a number of subskills. For example, to solve a physics problem, a student must be able to read the problem carefully and determine what information is being given, what the unknown is, and which equation should be used. He must be able to rearrange that equation to solve for the unknown, use the units (such as meters per second or Newtons of force) correctly, and use a calculator to arrive at an answer. If he cannot do every one of those steps, he cannot solve the problem.

When that happens — when he is unable to solve the problem — how he responds is critically important. If he has a fixed mindset, he will give up and tell himself that he just doesn’t know how to do this kind of work, or that he’s no good at physics, or even that he hates this class. To be successful, he needs to overcome his willingness to give up. Instead, he needs to be able to identify specifically what part of the process he doesn’t yet know how to do and take the necessary steps to learn that subskill. If, in the example above, he’s struggles with rearranging algebraic equations, then he needs to be taught how to do it and practice until he becomes proficient at it.

Effective remediation, then, must help him identify the specific problem area that he needs to work on and give him the ability to practice and learn it. Only then can he integrate the new learning into solving the whole problem.

The act of isolating the difficulty in this way not only teaches him this one particular skill, it helps him internalize the growth mindset; he learns that he can be successful if he applies himself. He learns, in fact, a great deal about how to learn.

Trusting the process.

If there is a process built into learning a new skill, as there is in the physics example above, then the student can practice that process until he is proficient at it. This allows him to take on problems that would otherwise be too daunting even to start. The trick is to trust that if he can successfully complete the first step — figuring out the givens and the unknowns in the example above — then that will lead him to the second step of choosing the appropriate equation. If he gets that far, then substituting in the givens into that equation isn’t too big a step, and so forth.

The analogy I find helpful is that of driving a car at night. You may not be able to see your destination, or even very far along the road, but if you have your headlights on, you can see far enough ahead to keep going and eventually reach your goal. The headlights are the process.

Incidentally, this focus on the process is an excellent, legitimate argument for why it is important to practice doing a certain skill, even when you think you have already mastered it. The more the process becomes second nature through repetition, the more useful it is as a tool when solving problems that are challenging.

Unlearning misunderstandings.

One of the most pernicious of problems occurs when a student has a preconceived notion that is, in fact, wrong. It often takes serious effort to replace that belief with the truth. If you want a quick education about this (or want to get the idea across to your students), watch “A Private Universe”, a film about how Princeton graduate students still believe their childhood misunderstanding about why the moon has phases. They believe, in spite of the best education, in spite of having been taught the true reason repeatedly, that it is the earth’s shadow that causes the phases. (It is actually the relative positions of the moon, earth, and sun.) The resilience of the misunderstanding among these highly educated people is startling.

Remediation, therefore, must help the student see the misunderstanding clearly in order to successfully challenge it and replace it with the correct understanding. Unlearning misunderstandings takes work, and remediation is where this work happens.

Articulating the correction.

Once a student has learned a new skill or has replaced a misunderstanding about a concept, he needs to check to see if he can explain it to someone else. The act of articulating what he has learned will check and verify how well he understands it. If he can teach a peer or someone at home, if he can write about it in his own words, then it is more likely that the material has been genuinely learned.

8.7 The Design of Remediation

8.7 The Design of Remediation

The remediation of a test depends on whether it is concepts or skills that are being tested. In both cases, however, remediation will consist of two phases. The first is a discovery phase, in which a student investigates his mistakes, tries to understand why he made them, and learns the correct concept or skill. Once that is accomplished, the student will engage in an articulation phase, in which he expresses what he has learned.

Both phases of remediation can take many shapes. They can be written or oral, done alone or in a group, at home or in class. You can be directly involved or completely uninvolved. For instance, if a student is working on improving a certain skill, he can do practice work and turn it in, or you can have him practice and then do some problems in your presence so you can offer him guidance and ask questions that will help him learn about the skill more deeply.

Whatever form of remediation you design, the principle goal is to reduce the hurdles facing a student in learning from his mistakes. The process should be relatively straightforward and as painless as possible. For instance, when a student suffers from test anxiety, making the remediation process feel less like taking a test is important. That may mean that the student can ask you questions while going through the process or that he can do the assessment without any time constraints. Conversation with the student about how the process feels is a good way to learn about how effective it is for him.

The next two sections describe methods of remediation for skills and concepts.

8.8 The Remediation of Skills

8.8 The Remediation of Skills

If a student is trying to master a specific skill, remediation will in general require more practice of that skill. If the goal is, say, learning how to factoring an algebraic equation, there is no substitute for factoring more algebraic equations. This practice will generally be followed by a retest to assess whether the student has, in fact, learned from his mistakes.

A central feature in designing remediation for skills-based content is a breakdown of a complex skill into its component subskills. As described in “Unit Contracts”, the learning process for such complex skills should be scaffolded around the introduction of a set of discrete subskills. In this way, the student can build towards complexity. He can be given feedback on each subskill in order to practice problem areas and build on his successes.

Similarly, the structure of both the test and its remediation should mirror that scaffolding and make the subskills visible. For instance, if a complex problem on the test requires of a number of subskills, each step can be considered an independent part of the test problem. Here is an example of the test question and answer showing the physics problem-solving scenario described above. Notice that the instructions for the problems indicate which steps are required, each of the steps is shown in sequence in the answer, and each is graded (with a “c”) separately.

Requiring the student to show each subskill explicitly in any complex problem and valuing each step as a part of the grade encourages the student to show all of his work. It also reinforces the student’s mastery of the problem-solving process and teaches him to trust that process when he gets stuck.

The test itself can thus serve the purpose of isolating the difficulty — helping the student to identify specific problem areas. Getting any step wrong tells the student that he must continue working on that subskill. Remediation can then allow the student to practice intensively, just as someone learning the piano will play a problematic musical phrase over and over until it is mastered.

If learning contracts are being used, a remediation contract can give a student the choice to practice only the specific subskills that he needs. An example of a remediation contract is described in detail in “Learning Contracts”.

The discovery phase of remediation should ideally be concluded with a checkup so that the student gets feedback that he has indeed mastered the skill before retesting.

Finally, remediation of skills must end with another assessment. The most practical means of assessing mastery is a retest, a second version of the original test, with similar skills-based questions. For students who struggle with test anxiety, this can be accomplished by having the student work through a problem similar to one on the test, explaining the process step by step to you.

The remediation of writing skills.

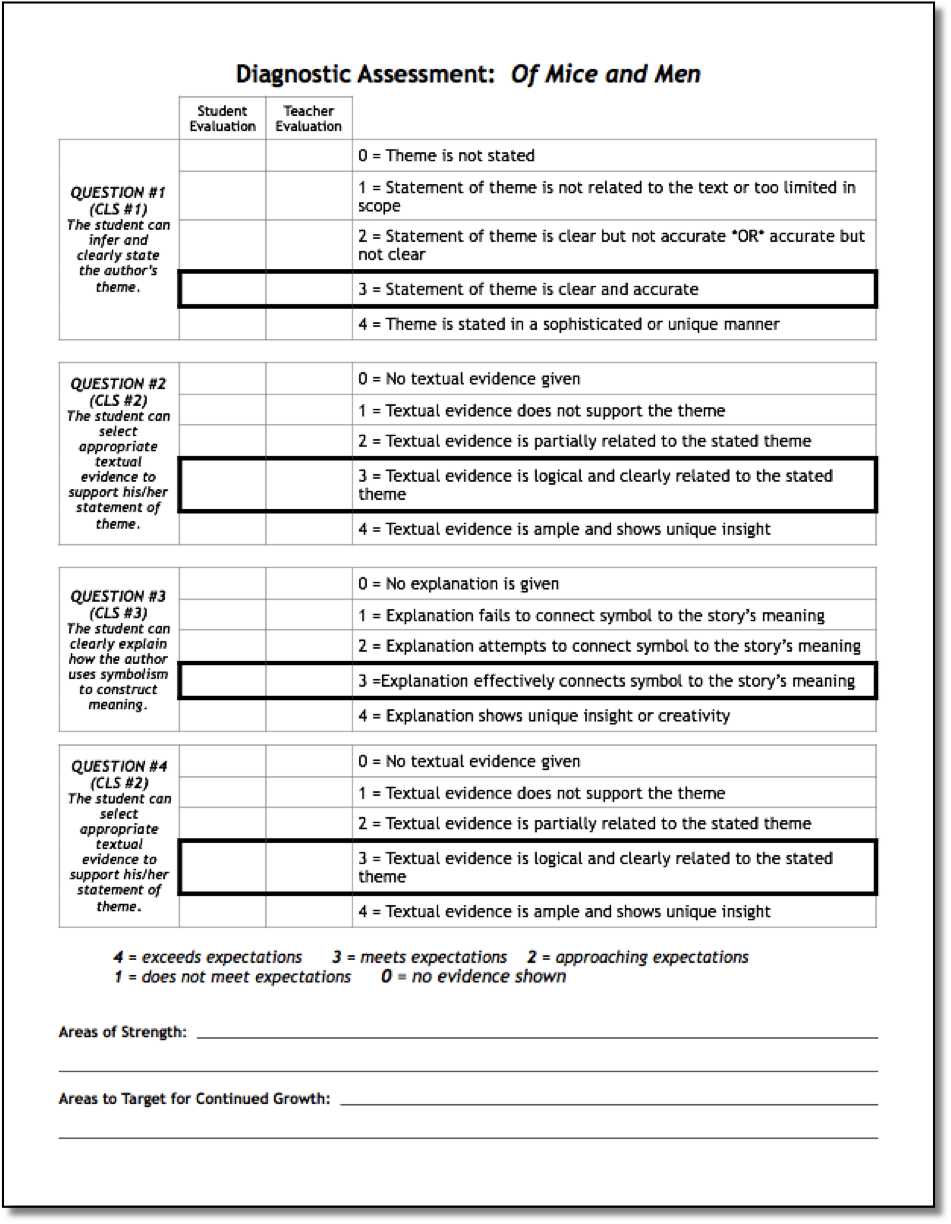

When writing skills are being assessed, the strategies described above may not be practical in identifying areas that a student needs to continue working on. In that case, a structure must be created that allows for a direct assessment of specific aspects of a student’s writing. An example is shown below. Once such an assessment exists, a remediation process can be constructed that allows a student to work specifically on the areas that he is struggling with.

8.9 The Remediation of Concepts

8.9 The Remediation of Concepts

Effective remediation helps a student identify his misunderstandings of a concept. It encourages him to articulate why he misunderstood the material. The process can begin with conversational learning. One approach is to have study groups review a test together, as described in the chapter “Study Groups”. This is a highly effective beginning of the discovery phase of remediation, in that it can give the student guidance and encouragement. He must then dive into the concept on his own — by rereading a relevant homework assignment, or watching a related video, or doing some independent research, for instance. This can also be accomplished with a remediation minicontract that gives the student a choice in how to explore the topic in depth. When this exploration is complete, a way of articulating the student’s mastery is needed. This is discussed in more detail below.

There are a number of possible options in guiding a student who is learning from his mistakes. These can be used alone or in combination. They can also be varied depending on the content of the test.

Here are some of those options:

He identifies how he should have learned the concept. Where was it introduced? What pages in the text book? What classroom activity? Which homework assignment?

He describes the source of the misunderstanding. Was there a specific diagram that the student misconstrued? A passage that he read and misunderstood?

He articulates the correct answer in his own words. Recycling quotes from the textbook are unlikely to help him learn.

He explains why the correct answer is correct. Again, this explanation must be in the student’s own words.

He creates an original test question about the same specific topic as the missed question, and answers it correctly. A student’s ability to to articulate what the question was really about is a big step in learning from the mistake.

Another aspect of metacognitive training requires the student to learn how he best learns. By paying attention to how he studied (unsuccessfully) for a test and exploring new options in studying for the next one, he can evolve towards more effective learning.

Care must be taken in choosing from the above options. It is important that the remediation process isn’t too time-consuming or daunting. It should not drive students away from this essential part of the learning process.

As an example of how to use these options, here is a test resubmittal form that I developed for my classes.

Notice that it not only requires a student to learn from his mistakes, but also to become more metacognitive about the process he uses for studying for the test.

There are, of course, other ways to help a student learn from his conceptual misunderstandings. One possibility is to have him compare and contrast his mistaken answer and the correct one. A quick way to accomplish this is by using a graphic organizer that requires him to identify what aspects of his wrong answer are the same as those of the right answer, and which aspects are not. Expressing what is similar and what is different can help him unlearn the misunderstanding. This technique can also be used any time students need to distinguish between confusingly similar concepts.

In the form below, the mistaken answer goes in the left shadowed box and the correct one in the right. Any overlapping aspects of the two answers, aspects that are true of both, go in the boxes between them. Any that are different go in the boxes to the left and right. Describing these aspects in a concise enough way to fit them into the form can force a student to zero in on the heart of the problem.

(Thanks to Research for Better Teaching, Inc. for this graphic organizer.)

8.10 Other Considerations in Test Design, Evaluation, and Remediation

8.10 Other Considerations in Test Design, Evaluation, and Remediation

"The test reflected what we knew, and that was it. You didn’t try to trick us into giving you wrong answers, you just wanted to see if we had mastery of the subject." —Tudor B., student

Avoid “trick” questions.

The purpose of testing should be to determine what our students know and are able to do. Questions that are intentionally misleading, or “distractors” in multiple choice tests, can serve to distinguish between more and less subtle understandings. Unfortunately, however, there is a cost. Such questions often feel manipulative, even mean-spirited to students. Besides, the distinctions sought by such questions are often based on the notion that the test is there to sort students into those who are more or less successful. If student mastery of the essential learning goals is indeed our highest priority, such sorting is unnecessary and counterproductive.

Don’t penalize domino mistakes.

If a skills-based problem has several steps, later stages often depend on getting the initial steps correct. Early mistakes cascade into mistakes throughout the problem and lead to a wrong answer, as seen in the problem below. Each step should be evaluated on its own correctness, given the results of the previous steps. A mistake at the beginning of the problem (marked with an “X”) carries through the problem, as indicated by the arrows dropping down. Given the results of this first mistake, the remaining steps in the problem are all correct (marked with large “C’s”).

Grading in this way takes more effort, but it helps draw attention to the subskill the student needs to focus on. It also reminds the student that he has done much or most of the problem correctly, as opposed to merely getting the correct answer.

The role of conversational learning in formative assessments.

As described in “Study Groups”, one of the most important areas in which students can help each other learn is in going over tests. While it takes enormous trust (which must be cultivated), once a student can reveal his mistakes and misunderstandings to a group, the conversation that follows can be some of the most effective learning he will do. It is a prime opportunity to identify and explore what he hasn’t learned yet and to dive into the details of his misunderstandings. It is an effective beginning to the remediation he must do.

Above and beyond: to test or not to test.

If you practice differentiated learning in your classroom, while some students are focussing on remediation, others will be working on enrichment activities. Should those activities be assessed? In general, the answer is no.

No one should ever be penalized for having the initiative to volunteer to take on more challenging work. If a student does badly on an assessment of the enrichment work he did, he will be disinclined to volunteer to do it again.

There are, however, circumstances where assessing above and beyond work may make sense. It may be useful for a student to receive ungraded feedback on an assessment of enrichment work to help him see how well he understands it. This is particularly relevant if that work is related to a long-term goal such as preparing for an AP exam. (See below).

Another circumstance when this practice may be valuable is if you are teaching a “de-tracked” class that includes both regular and honors level curriculum. It may be that the above and beyond work is expected of students enrolled at the honors level, and their grades should incorporate an assessment of that work.

Diagnosing poor test results.

If your students are self-evaluating their work, a teachable moment in directing a student towards realistic self-assessment may arise if his results on tests are much poorer than his reported results on doing the same material in his homework. This discrepancy may occur for a number of reasons. The student may have knowingly claimed to understand the material better than he actually did because he didn’t want to do any additional work. This problem tends to be self-correcting, but warrants a conversation between you and the student.

Another possibility is that he suffers from test anxiety and can’t reproduce his success with the homework under the pressure of a test. Working to alleviate test anxiety can be helpful, as described below. It might also be possible to find an alternative form of assessment that the student won’t find so frightening.

A third possibility is that the student simply isn’t metacognitive enough to know he hasn’t mastered the skill yet. A typical example is when he uses the helpful hints but doesn’t recognize that he can’t do the work independently yet. This is a problem of self-awareness and requires practice on his part to pay better attention to his habit of glossing over problems.

Alleviating test anxiety.

Many students find tests stressful, and some experience mild panic attacks on a regular basis. If we want to make our assessments accurate, as well as avoid causing our students such distress, we have to directly attack the problem of test anxiety.

We can begin by explicitly changing the meaning of tests. Once students understand that tests are not a way to accumulate points, but rather a check-up on their progress in learning the material, the pressure to do well is often reduced. Students understand that making mistakes is not a permanent failure; they can recover from a low score without penalty or shame.

It is also important to teach students to break the trance that many of them go into while taking a test. Teaching them to take a break every now and then, breathe deeply and extract their minds from the test can give them more clarity. Breathing well is particularly important in reducing panicky feelings; it increases oxygen flow to the brain and allows students to think more clearly.

Lightening the mood during testing is also a good strategy. Reminding them that this is only a test, and that when they are 40 years old, looking back on their lives, this moment will have receded into complete insignificance, helps them get some perspective. I would often interrupt them when they least expected it and tell them a bad joke to get them to groan and laugh.

Allowing enough time for the slowest students to finish successfully can help alleviate a particular source of pressure. This raises the question of what students who finish more quickly should do once they are done with the test. In my experience, there should be a number of non-distracting activities available, including reading, internet research, writing about current events (described in detail in “Tools for Teachers”), or working on long-term projects.

It is often worthwhile to hold a test-taking workshop for students who are particularly troubled by test anxiety. You can identify those common areas that a student may feel panicky about. He may worry about how much time he is taking to answer questions and get paralyzed because he is afraid he won’t be able finish all the problems. He may get stuck staring at a hard question and not get past it, rather than leaving it behind and working on easier questions that he can do relatively quickly. He may need a different setting, sitting in a different place or listening to music. He may need you to stop by periodically and get him refocussed, so that he feels supported. The trick is to help him isolate his difficulty with tests and to identify and put coping strategies into place.

Finally, when a student says “I’m just a bad test taker”, he is telling you that he has a fatalistic, fixed mindset and doesn’t believe that there is anything that he can do about it. Working with him to identify where the problem lies can help him not only to do better on tests, but also to become less fatalistic and more optimistic in his attitude. In other words, challenging a student’s test anxieties can serve as a means of shifting him from a fixed mindset to a growth mindset.

Remediation should be voluntary whenever possible.

If a student chooses to learn from his mistakes on a test, it is much more likely that it will be meaningful for him than if remediation is mandatory. As always, we are trying to have students both master the content and grow as people as much as possible. Becoming self-directed and feeling a sense of ownership over the learning process are important aspects of that growth. It is paramount for the teacher to encourage responsible, internally motivated choices.

On the other hand, there may be students who, for various reasons, choose not to learn from their mistakes. In particular, a student with a fixed mindset may feel hopeless about the prospect of improving his understanding through personal effort. He may simply not believe that the extra work will improve his performance. For such a student, it is best for the teacher to intervene. Making remediation mandatory for him, preferably with a lot of support, will not only improve his mastery of the content, but will also help him break the fatalistic hopelessness he feels about school. The key here is to not offer too much choice. If you plan open work time within a unit, create an in-class remediation workshop for every student who scored below a given threshold on a test. Even simpler, have study groups review the tests together, going over every question that every student in the group got wrong. In this way, even a resistant student will be forced to begin the process of learning from his mistakes.

You may also want an upper threshold on who can do remediation. If a student gets an “A-“ on a test and wants to keep working on the material, he is probably not doing remediation for the sake of learning from his mistakes. Rather, opening the process up to him is most likely reinforcing the bad habits of doing school — he is going to squeeze a few more points out of the system. Of course, this is not always the case, and whether you have an upper threshold for remediation will depend on what you perceive your students’ motivations to be.

Remediation and student maturity.

As always, the amount of freedom offered to a student must be attuned to his readiness to act responsibly. Younger, less mature students should have the remediation process spelled out explicitly, with little leeway in how it is accomplished. For older, more responsible students, remediation can be more varied and responsive to their individual needs. As the year progresses and students become accustomed to the increased level of responsibility and freedom to steer their own learning, more and more choice can be made available to them.

Differentiated remediation.

Unit contracts offer the flexibility of allowing students who need remediation to continue working on the previous unit while the class moves on to the next unit. A student’s ability to work on past and present topics simultaneously requires learning how to manage his time well. Many students will initially need support in learning this skill.

Remediation and effort.

The purpose of remediation is for students to learn from their mistakes. This process can be complicated and may take a great deal of time. On the other hand, when the remediation process requires too much time and effort, even highly motivated students will not do it. A balance must be struck between having the process be rigorous enough to be meaningful and straightforward enough to be worth the effort in the student’s eyes.

In order to maintain forward momentum and cohesion in a class, remediation needs to have a well-defined time limit. In my experience, completing all review work within a week of the test is a reasonable amount of time.

Remediation and grades.

How to evaluate remediation efforts is a subjective call. Taking the higher of the two test grades — the original test and the results after remediation — may cause students to not take the first test as seriously, particularly if the classroom culture isn’t well established. On the other hand, the grit required to pursue learning after having made mistakes is an important attribute that should be legitimately rewarded.

In my practice, I found that taking the average of the two scores — allowing a student to get “halfway to perfect” — was a reasonable compromise. I also decided that if a student’s test score went down after remediation, I would keep the original test score so as not to discourage students from learning from their mistakes. They should never be punished for showing tenacity.

8.11 The Problem of Standardized Tests

8.11 The Problem of Standardized Tests

Many teachers feel they can’t take the time to do formative assessments because there is too much curricular pressure. They may feel driven to prepare themselves for a standardized test at the end of the semester or year that assesses so much material that they feel there is no time for anything but marching through the curriculum as fast as possible.

This raises numerous questions. Is mastery of what is being tested a realistic goal for every student? Given the people in the room, the time constraints, and the wide range of readiness and motivation to learn, can all students be successful at meeting the prescribed standards? In my experience, working with many teachers in many disciplines, the answer is invariably no.

If we are expecting students to meet standards that we know are not realistic goals for every student, then they aren’t standards. By definition, standards comprise what we expect every student to know and be able to do. At best, the current “standards” are aspirational — they are what we would like students to accomplish. Unfortunately, they also serve as filters, sorting children into more or less successful students. This sorting satisfies a larger purpose in the educational system, of course. But, as described above, such sorting also does enormous damage. Pushing through the curriculum to cover everything for the standardized test requires abandoning self-directed learning. It means that we cease to respond to the needs of struggling learners — there simply isn’t enough time. Teachers are forced to leave the wreckage behind.

Since standardized tests are a reality that teachers have little or no control over, the task at hand is to optimize a student’s chances of doing well on these assessments while not abandoning the central purpose of self-directed learning. Fortunately, there is a way to do this.

Unit tests should be based on learning goals that are realistic for all your students. Through differentiation techniques like learning contracts, faster, more successful students can do enrichment activities which cover everything expected on the exam. Since they are working at an appropriate level of challenge, they will be well prepared for the standardized test.

At the same time, because the learning goals are realistic, slower students will have a solid base of learning, even if it is on a smaller scope than will be seen on the standardized test. As a result, they will do much better under this system than they would have under the old approach of marching through the curriculum so quickly that they would learn very little. They will also have more self-confidence, too, and will be better prepared to take advantage of systematic reviewing (i.e. cramming) that will occur before the exam. Now that review will be much more useful for them.

Raising standardized test scores does not require abandoning self-directed learning as the central purpose of your class, nor abandoning the students who struggle most.

8.12 Differentiated Exam Prep

8.12 Differentiated Exam Prep

The Challenge of Summative Assessments.

In general, tests should be formative in nature, an integrated part of the learning process. However, as described above, some assessments tend to be summative: a snapshot of a student’s progress. Nevertheless, all tests are excellent opportunities for differentiated learning. The review process leading up to the test should be designed to be responsive to each student’s individual needs.

The Practice Test.

The first step in preparing for a exam is to assess student readiness. It is essential that each student identify what he has learned and what he doesn't know yet. A practice test of all the major concepts and skills is needed to determine how he should prepare for the real test.

Like all checkups, the practice test provides feedback both for the student and for you; he needs to know what specific work to do to prepare for the test, and you need to know what role you will play in the review process. If, for instance, there are topics that a large number of students haven’t mastered, a whole class review may be called for. If a smaller number of students are struggling with a different topic, it may be useful for you to run a workshop on that topic for those students.

Here are some guidelines for creating the practice test:

The test should address all the major concepts and skills on the exam - there should be no big surprises.

It must be as brief as possible. The more time spent taking, grading, and going over the test, the less time remains for the actual review process.

Like all checkups, the practice test should not be graded. Its sole purpose is to steer each student’s review process. Feedback is more effective when it is separated from grades.

The practice test can be used to prepare students for both the content and the format of the test. Getting accustomed to the format is particularly important for high stakes tests such as the ACT and AP exams.

The practice test can be made as similar to the actual exam as needed. Taking previous ACT or AP exams, for instance, is excellent preparation for the real thing.

The idea of a practice test should be introduced to students as a way for each of them to identify what they need to work on during the review period.

Evaluating and Reviewing the Practice Test.

How the test is evaluated and used depends on how self-directed your students are. If students are accustomed to reviewing tests in study groups, it is optimal to give them answer keys as soon as they have finished taking the test and have them self-evaluate it immediately. They can then discuss the questions they got wrong within their study group.

If they are not yet independent enough to self-evaluate, you can evaluate their work (remember, no grades) after class and hand the tests back the next day, at which time students can review them in groups, if that’s appropriate. Such a review will often result in useful learning, but as a minimum, it should identify specifically what each student must work on to prepare for the test.

Differentiated Exam Prep.

A central purpose of the practice test is to lead to an individualized review process. For every area that a student struggled with on the practice test, there needs to be specific work available. A review packet can be created to include all such work. Obviously, each student should only do those parts of the packet that are useful for him.

One approach to organizing the review process is to create a mini-contract that acts as a cover sheet for the review packet and includes all its contents. The contract can link the specific problems the student got wrong on the practice test with the appropriate items in the packet.

If students are sufficiently independent and self-directed, they can choose what work they need to do by themselves. If they are not ready to do this, you can retain complete control over directing their review process. While you are evaluating their practice test, you can mark the review contract to indicate which items in the review packet they should do. The next day, you can hand the contract, the review packet, and the practice test back at the same time.

Some guidelines on creating the review contract and materials:

The items available in a review contract need to reflect all the content found on the practice test. If a student got a problem on the practice test wrong, there should be a way for him to learn from his mistake.

The items in the review contract can often be review materials you already have. Rather than having every student review every aspect of the exam, however, the review contract allows him to focus specifically on those areas that he still needs to work on.

If you have been using contracts throughout the year, the review contract for a semester exam can also include items from previous contracts.

Leave blanks in the review contract so that items can be added as needed, either by the teacher or the student in conversation with the teacher. This is particularly important the first few times this approach is tried.

A review contract should also include enrichment items so students who did well on the practice test can deepen their mastery. Those students can serve as “resident experts” or tutors for students who are struggling. A contract should offer peer tutoring as an optional item for such students to encourage them to share the wealth.

Finally, review contract items can include outside support, such as attending teacher review sessions or peer tutoring outside of class, as well as the use of study centers or any other school-wide support.

The review process itself may consist of open work time that allows students to pursue whatever contract items they need. This work can be done individually or in groups. It can also be done in part as homework.

In addition, the review process should encourage conversational learning whenever appropriate. Teacher-generated questions about the review packet can serve as springboards for conversations within study groups or other ad hoc groups. There can be workshops to reteach specific contract items. These can be led by the teacher or by students who are proficient in that content.

Collective Cramming.

In general, one of your most important tasks as a teacher is to help students replace cramming with genuine learning. However, there are circumstances when cramming is appropriate and should be embraced.

If part or all of the exam is standardized, for instance, there may be topics on it that you have not taught in your class. Helping students do well on those topics means introducing them as quickly and effectively as possible to the material, knowing that they may not genuinely learn much in the process. In other words, you are helping them cram for the test.

This is admittedly teaching to the test. However, it can be argued that as long as standardized tests are assessing material that does not fit into the course you are teaching, that is exactly what is called for. A great deal of test prep for standardized tests like the ACT or AP exams is essentially cramming. Such reviews are common, and even required. No one truly expects students to absorb and remember the new material learned these during test prep sessions.

Since cramming violates the basic philosophy you espouse, you should discuss why you are doing it with your students. The conversation can begin with an honest statement: you are required to give this particular test and cannot fully control what is on it. Your highest priority as a teacher has been to make sure that students are genuinely learning the material, rather than moving through the content at the pace necessary to cover everything on the exam. Rather than penalize students for that decision, your goal is to help everyone to do as well on the test as possible. In other words, for topics on the test that have not been covered in class, cramming needs to become a common purpose, a group project. Your collective goal is for everyone to do as well on the test as possible, and that means putting those topics into working memory. As a fringe benefit, some students will be ready and able to genuinely learn those topics during the brief time allotted for them.

8.13 Example: Reviewing for a Psychology AP Exam

8.13 Example: Reviewing for a Psychology AP Exam

The example below describes a three day review for an AP exam in psychology.

Before Day 1: Students receive an overview of exam topics in the form of a review packet. They are given a practice test online to complete at home.

Day 1: Students immediately get into study groups with answer keys to the practice test. Each student evaluates his own test and determines the areas of concern to work on. The group discusses every question that any group member got wrong or didn’t understand. The basis of the conversation includes the correct answer to each problem, the reason why it is correct, and the reason each student’s wrong answer was chosen. Each student then fills out the form below to decide on what his focus for review is going to be.

Students are given a summary sheet, also below, that identifies the appropriate activities for any area of concern.

The rest of the period is open work time. Students can work on contract items individually, with peer tutors, or in groups of their choosing. Workshops can be offered on specific topics, to be led by the teacher or by students who are proficient at those topics. Outside resources, such as study centers and review sessions outside of class, are offered as additional support.

Day 2: Open work time continues.

Day 3: Answer keys are provided for all contract items that are skills-based. A whole class review is possible at this point, with the proviso that students who need to continue working on contract items or students who are already well-prepared for the test may opt out if they choose. A pep talk and advice about test-taking may be appropriate.

8.14 Other Sample Exam Reviews

8.14 Other Sample Exam Reviews

Example #1: ESL Three Day Review

Day 1. Since the exam for this course consists of writing an essay that displays the grammatical and writing skills learned in class, the practice exam can be identical in nature. Before handing out the practice test, go over how it will be evaluated so students know what you are looking for. Give them the practice test with plenty of time for the slowest students to complete it.

After class, evaluate the practice test and fill out a review contract for each student to indicate what work he needs to do based on what he struggled with on the practice test. For students who need to work on grammar and other mechanical issues, provide review items that focus on practicing those mechanics. For broader issues, such as difficulty in writing a strong lead sentence, offer review items that allow students to practice those skills. For students who are successful on the practice test, contract items should include both enrichment items and opportunities to teach others through peer tutoring, study group work, or by leading workshops.

Day 2. Return the practice test with a review packet and the contract as a cover sheet. Have students get in groups and review the practice test. Once they have finished, have them start working on the items indicated in their contracts. This can consist of individual work, peer tutoring, study group discussions, or workshops on specific skills. For contract items that allow students to practice skills, answer keys should be given to them once they have completed those items.

Day 3: Continue open work time. Remind the class of the specific learning goals being assessed. Give a pep talk and advice about test-taking to help students who suffer from test anxiety.

Example #2: Algebra Five Day Review

Day 1. Give a brief summary of what will be on the exam. Split the material into halves. Give Practice Test #1, which covers the first half of the material.

Evaluate the practice test after class and fill out a review contract for each student to indicate what work from the review packet he needs to do.

Day 2. Return Practice Test #1. Have study groups review the test with an answer keys, if appropriate. Hand out the review packet and the contract. Give students open work time to address the review packet items they need to work on.

Day 3: Continue with open work time. Give Practice Test #2, which covers the remaining material. Have students hand in their contracts so that they can be given further work to do based on the results of the second test.

Day 4: Return Practice Test #2 and their revised contracts. Continue with open work time.

Day 5: Cram for any topics which have not yet been covered with the whole class. Remaining time can be used in open work time or a Q&A session. Give a pep talk and advice about test-taking.

Example #3 : Spanish Five Day Review

Give a pretest two weeks before the exam. Have students take it at home and return it before the review period.

Evaluate the test and choose work on the contract for each student. based on what he missed on the practice test.

On the first day of the review, hand students the graded test with an answer key. Have them review the problems they got wrong using the answer key so that they can start learning from their mistakes immediately. Hand out the review packet with the contract cover sheet, indicating what specific contract items they need to work on.

For students who aced the practice test, create structures so that they can teach others right away. This can include peer tutoring, study groups, and being workshop leaders.

For students who did fairly well, have them do the necessary work in the packet, then teach the topics they struggled with to reinforce their learning.

Organize the review process on a day-by-day basis, responding to what students need.

8.15 Tenets of a New Paradigm

8.15 Tenets of a New Paradigm

Tests alone are not a reliable measure of genuine learning.

They do not distinguish between material that has been learned and that which has been memorized and will be forgotten in a short while. True learning must be evaluated through a range of activities and assessments, of which tests and quizzes are only a part.

Tests are best used as an integral part of the learning process, not an after-the fact status report.

They tell the student what they have learned so far and what they still need to learn. Redefining tests as feedback for the student helps make tests meaningful and useful. When there are comfortable and practical ways to learn from his mistakes, a student can appreciate a test as an important part of the learning process.

All tests should be formative, unless there is a compelling reason for them to be summative.

Why not let them learn from their mistakes? It’s an important part of the learning process.

Test grades are not final until a student has mastered the material or stopped trying.

No student should be forced to leave the wreckage behind. On the other hand, there have to be practical limits as to how long the remediation process can take.

The remediation process is as important as the test itself.

It is how students learn from their mistakes.

Time pressure should never be a part of testing unless you are explicitly testing students’ ability to work under pressure.

Time pressure adds to test anxiety, especially for students who are struggling or simply work more slowly. Tests should be designed so that the slowest students have enough time; the test is more likely to show what they have learned.

If you can’t say it, you don’t really know it.

Asking students to articulate what they have learned is a legitimate function of tests.

The habit of cramming, regurgitating on tests, and forgetting can be unlearned.

When the techniques of self-directed learning are functioning well — e.g., the appropriate classroom culture exists, the work students do trains them to be metacognitive learners, and conversational learning is commonplace — the test becomes a check-up of how well the learning process is working for each student. If it is working well, a student may not need to review much before taking a test because he has actually learned the material. Cramming becomes superfluous.

Formative testing cultivates grit.

By encouraging students to continue working through difficulties and failures, the remediation process helps them internalize a growth mindset and a trust that if they keep working they can become successful.

Reducing test anxiety makes for better education and more accurate assessments.

There are ways to make test-taking less stressful. Eliminating time constraints, reducing tight control over student behavior during the tests, and reminding students that they can recover if they don’t do well are all helpful in reducing test anxieties. Relaxed students show what they have learned more accurately, and they are happier in the process. There is no reason why they should have to suffer while they are showing how much they have learned.